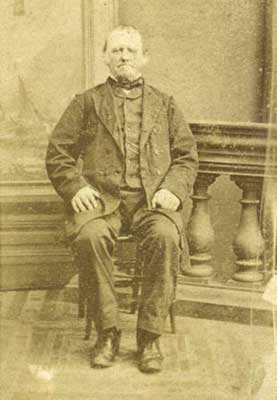

Stephen Grant b1811

We now enter more recent times, and Stephen is the first person who has been known by people who were alive when this research started. He was the third son of John Grant (b.1770) to survive and raise a family.

He was born at Towra, Shinrone on 19th August 1811. There is virtually no information on his childhood. The community of Protestant labourers that existed 200 years ago at Shinrone has all but disappeared. Of the labourers’ cottages at Towra, which is about a mile from Shinrone, only a handful of ruins remain. The old map shops a dozen or more such cottages along the Towra road, but none remain.

The present Church of Ireland at Shinrone replaced the old medieval church on the same site, architectural fragments of which can still be seen in the church grounds. At a meeting of the Rector, Church Wardens and parishioners of Shinrone in 1811, it was decided to build a new one capable of accommodating a congregation much larger than the old one. The building of the new church began in 1819, a year in which the Board of Fruits, which administered church grants, spent £30,000 of which £2,300 went to Shinrone. It was probably designed by the architect Bowden, who followed the common formula for Board of First Fruits' work, by providing a large rectangular hall for the church itself and a square tower at one end.

Shinrone Protestant Church in 2008

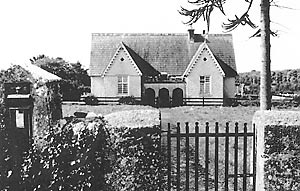

It is not known where, or indeed if, he went to school. But the nearest school would have been the two-roomed school, built as a private school to accommodate 100 pupils which had been established in 1826 by the Earl of Charleville and Francis Trench of Sopwell Hall. It became a National School under the Board of Education in 1832. Stephen would have already started work by 1826 when this school opened. However it does bring up the name "Trench", and the Trenches were a part of Stephen Grant's life, for better or for worse, for the whole of his life.

Sopwell School

|

|

|

|

|

The Trench properties in the area Sopwell Hall (top left) Cangort House (bottom left) Cangort Park (top right) |

Branches of the Trenches owned Cangort Park, not to be confused with the adjacent estate called Cangort (owned by the Atkinson family, inter-married into the Trenches). The Atkinsons were the Grant's landlords at this time. Guy Atkinson was the landlord at this time, and he was born on 14 Jul 1800 in Cangort, Shinrone. He died on 28 Nov 1859. He married Margaret Trench on 24 Oct 1839. The tenant system relied upon a large number of tenant farmers supporting each grand house. Cangort Park had 300 acres and Cangort had 500 acres. The estate included a large fruit orchard, massive barns and rich gently rolling farmland. Sopwell Hall came into the possession of the Trench family in 1796 when Francis Sadlier's daughter Mary married Frederick Trench. He was later Lord Ashtown. He left Sopwell to his younger brother Francis Trench, who lived here till his death in 1829. William Stuart Trench, son of Rev Trench, Dean of Kildare and brother of 1st Lord Ashtown, was living in Sopwell Hall in 1840. He rented it from his cousin. All these "big houses" were within two to three miles of Shinrone. One can see how Stephen Grant came to work on Lord Ashtown's Woodlawn estate.

Life was not easy, from an article about "Famine and Tithes in 1822" " By 1822, little had changed with a similar number of complaints despite the presence of the yeomanry. In February, Major Powell in Shanavogue submitted a sample of a notice objecting to tithes in the parish of Shinrone but by the middle of March he commented on the tranquillity of the district attributing peace to the recently enforced Insurrection Act. Also in March, the petition of the local justice of the peace in Edenderry, Mr. J. Brownrigg, was successful in obtaining a military station for the eastern part of the county. He stressed that a permanent force was needed indicating the uselessness of bringing military into the county only to take them out again. In late June 1822 a report verified that hunger and disease were stretching available resources while violence became more common as men became more desperate. Major Powell had written on three aspects which drew attention to the problems worrying county officials: firstly, that violent outrages were increasing although a man indicted for a local murder had been apprehended, next that a fever hospital to cope with typhoid had been established and thirdly, that he strongly was of the opinion that local distress was attributable to the lack of employment rather than a shortage of food."

The Green Ribbon Meeting of 1828. In 1792 the rectory and vicarage of Shinrone were united to Kilmurray, and these were afterwards episcopally united to the rectory of Kilcommon. It is related there were only ten houses in Shinrone in 1640. In 1828, the excitement over the Roman Catholic Emancipation Act was intense all over Ireland. A great meeting was held in Roscrea, when the men paraded in green ribbons, determined on a similar demonstration at Shinrone, at that time one of the few Protestant towns in the Midlands. When the inhabitants of Shinrone heard that thousands would march on their town from Galway, Tipperary, Kilkenny, and Queen’s County, they fortified themselves. The doorways and lower windows were barricaded. Sashes were removed from the upper windows, converting them into embrasures for musketry; and on the other hand the “Green Boys” swore, that march through the town they would, let the hazard be what it might. However, on the 27th September, the day previous to the meeting, Lord Rosse, of Telescope-making fame, then Lord Oxmantown, received a despatch from the Duke of Wellington, at that time First Lord of the Treasury, and the Marquis of Anglesea, Lord Lieutenant, directing him to take to Shinrone a competent force to preserve the peace. When the preparations for the drafting in of two regiments besides police and some cavalry, by Oxmantown, became known, and news of this description circulated, the contemplated procession was dropped, only a small body persisting, but on getting close, they were prevailed upon to return. Thus ended a raid, which for the time, created discussion and excitement.

After the passing of Catholic Emancipation in 1829, it was reasonable to expect that there would be an improvement in the economic and social life of the country. However, this was not to happen quickly. Catholic tenant farmers and cottiers considered it most unjust that in addition to paying their rent, they should still be forced to pay an annual tax on the produce of their land, known as the Tithe, towards the upkeep of the Protestant Established Church. Moreover, they resented the manner in which the Tithe was assessed and collected. It was levied on tillage, on which the majority of people depended for food and rent, whereas the large "graziers", invariably Protestant, were exempt from paying the tax. Another reason for discontent was that the valuing of crops for Tithe purposes was left to the despised Proctors, or tax collectors, who got a percentage of the money they collected and often valued unfairly in their own interests. The Tithe varied from district to district and from time to time and was paid in kind, in corn mostly and potatoes. (Ignatius Murphy, The Diocese of Killaloe 1800-1850, p 14)

In November 1835, Mr. Smith, agent for the Rev. William Brownlow Savage, Rector of the Union of Shinrone, Kilcommon and Kilmurry, filed two bills for tithes against Mr. Thomas Tiquin, a prominent businessman from Rusheen, Kilcommon. The foundations of the mill and house where Tiquin and his family carried on a successful milling business can still be seen at the Three Roads in the townland of Rusheen. The total sum claimed amounted to one pound, twelve shillings and eight pence. Tiquin refused to pay the tithes and a court case followed. Despite being defended by the eminent Q.C., Mr. Rolleston of Glasshouse, Tiquin lost his case, was arrested, and confined in the barracks at Shinrone, before being transferred to Newgate prison now known as Kilmainham. It seems that Tiquin was convicted on a legal technicality, which was regarded as being most unjust at the time. The trial and imprisonment so affected Tiquin, that despite being 'one of the finest young men in the King's County, upward of six feet two inches in height, and the idol of his neighbourhood', he died shortly after his imprisonment. (Valentine Trodd, Midlanders, pp 13-14)

Daniel 0' Connell and the Catholic Association, realised that the indignation which the trial and death of Tiquin had aroused could be used to bring added pressure on the Government to abolish the Tithes. The coffin, borne in a plain hearse, drawn by four black-plumed horses, left Dublin on Thursday evening. Four placards were attached to the hearse bearing the inscription, "Funeral of Mr. Thomas Tiquin of Shinrone, in King's County, who died on Thursday 30th May, 1837, while under imprisonment in the Four Courts, Marshalsea, Dublin.

While on its way to Shinrone, it stopped overnight twice. Thousands of people, on foot, on horseback and in cars, carriages and gigs, accompanied the cortege. On the Saturday, Tiquin's two brothers, together with his wife Maryanne and other relatives arrived in Roscrea to await the arrival of the funeral. The Catholic Association had arranged that the funeral should proceed through Shinrone and Dunkerrin, but the family decided that the remains should be taken directly from Roscrea to Birr and then on to the family burial grounds at "All Saints" in Banagher. On the Saturday, while hundreds prayed in the chapels of Shinrone and Roscrea for the "victim who so nobly sacrificed himself for his country", hundreds of friends and neighbours from Shinrone proceeded to Mountrath, Castletown and Borris-in-Ossory to accompany the remains to the church in Roscrea.

On the Saturday night, the funeral made its way to Birr where the Roman Catholic Bishop, after addressing an estimated crowd of seventeen to eighteen thousand people, advised them to disperse quietly. It was Bishop Kennedy, then Fr. Kennedy, together with Thomas Lalor Cooke who had been responsible for stopping the Greenboys march on Shinrone in 1828. It was three o'clock on Sunday when the funeral reached the "All Saints Well" burial ground, Banagher, where Tiquin was laid in his grave. On its way to the burial ground the hearse had to stop for half an hour to allow the people from Shinrone, Cloghan, Banagher, Roscrea, Lockeen and Durrow to arrive. It is estimated that in all, 200,000 people took part in the funeral on that day. (Leinster Express, 10th June 1837)

In 1838, the following year, the Tithes were abolished. Tiquin became known as The Last Tithe Martyr' and it seems certain that just as the march of the Greenboys was influential in hastening the passing of Catholic Emancipation, the imprisonment and subsequent death of Thomas Tiquin accelerated the abolition of the Tithes.

Stephen married Mary Ann Piper on 2nd December 1837. She came from Portland, Portumna, the daughter of Charles Piper (a farmer) and Ann Brown. She had been born 5 Oct 1821 at Portumna, and was only just 16 when she married Stephen and he was 26. Portland House, for whom her father worked is in ruins today.

|

|

|

| Houses in Towra have all rotted away |

Ruin of Portland House in 2007 |

Stephen and Mary Anne lived at Towra until 1840 and their first two children were born there. An internet search revealed that Richard was born in Dorrah in 1843. We do not know where the other children were born, but we do have their dates of birth from family records. From the fact that their son James death certificate says he was born in Roscommon and their son John was living in Balinasloe when he married in 1863, it looks as if the family were at Balinasloe at least for some of the period between 1858 and 1868, when Stephen is first noted as a tenant at Kilconnel, Co Galway. There is no sign of Stephen in Griffiths, which should have picked him up during the 1850s if he had been a tenant somewhere.

The connection I feel is the Trench family for whom the Grants worked in Shinrone, and who had scattered property in the area. The famine struck hard over the period 1845 to 1849, and this will have caused Stephen Grant to move. The Trenches, as well as Woodlawn, Kilconnel, also owned Garbally, Ballinasloe. In addition Lord Ashtown's cousin was married to Guy Atkinson, the Grants' landlord at Towra. Additionally Trenches owned Cangort Park and Deerpark where other Grants were tenants. Good loyal Protestant workers were at a premium at the time of the Land League, and Lord Ashtown had the reputation of being a hard man. I feel that the probability is that Stephen and his family moved in the employ of the Trenches.

When the 1st Baron Ashtown died in 1840, he had lived in England since 1800 and was effectively an absentee landlord. He was succeeded by his nephew Frederick Trench, who was the 2nd Lord Ashtown from 1840 until his death in 1880. The house was extended in the 1850s when the 3 storey house was refaced and embellished in the Italianate style, and enlarged by 2 two-storey wings three-bay wings. Building on such a lavish scale was rare in post-famine Ireland. Stephen Grant became gatekeeper on this enlarged Woodlawn estate, and the family lived in the little castellated gate lodge, known locally as Grants Castle. Stephen's children left home in rapid succession around this time. Stephen first appears in Woodlawn records in 1868. But may well have been there earlier, as we do not know his whereabouts between 1850 and 1868. The work at Woodlawn presumably created much new employment, and a working class Protestant such as Stephen would have been able to get employment on the estate without difficulty.

And it was Frederick Trench's grandson who became the 3rd Lord Ashtown from 1880 until his death in 1946. Further large sums were spent by him in the late 1800's on gardening projects, outbuildings, land drainage and livestock. This created employment for up to 300 people at times. However he ran into financial difficulties and by 1922 was forced to action off moveable property. The 3rd Baron was unpopular with his Catholic neighbours and had to be given police protection. He was deeply opposed to the United Irish League and in a published letter claimed that it was run by "the Church of Rome” He called on "loyalists and Unionists" to fight for their freedom against the power of Rome.

Stephen's son John had already left Ireland around 1865 to Durham in England, followed by brothers Charles (soon after 1867), Richard (before 1870) and Stephen (late 1870s). My great grandfather Thomas joined the Dublin Metropolitan Police in 1871 and moved to Dublin. William also went to Dublin, Anne to the USA. James went to Australia around 1875. In fact between 1850 and 1900 the population of the area fell by 48% largely through emigration.

There was a school at Woodlawn, which in 1862 had a roll of 120. The bulk of the pupils were Catholic: 104 Catholic, 16 Protestant.

|

|

|

| Woodlawn 1890 |

Woodlawn 2008 |

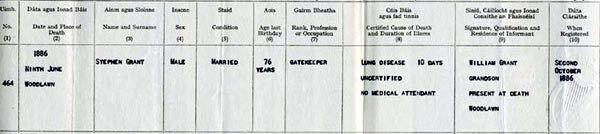

He died on the 9th June 1886, the day Mr Gladstone’s last Home Rule Bill for Ireland was defeated in the Imperial House of Commons. The progress of the Bill was watched with anxiety by Irish Unionists, particularly the Protestant class. The vote took place after two months of debating and, on 8 June 1886, 341 voted against it (including 93 Liberals) while 311 voted for it. Parliament was dissolved on 26 June and the UK general election, 1886 was called. Charles Grant said that during his grandfather’s last illness he continually spoke of the Bill, and his last words to Thomas Grant before he died were “Thank God” when he was told that the Bill had been rejected.

When Stephen died 9 June 1886, his wife lived on in the gate lodge until she died in 1913. Their two youngest, and unmarried children, Robert and Elizabeth stayed on there until Robert's death in 1935. The family's connection with Woodlawn ceased at that point. Elizabeth moved out, staying with her brother Thomas (my great grandfather) in Dublin until his death in 1940.

|

|

|

| Woodlawn Gatehouse in 1975 |

Interior of Gatehouse in 2008 |

|

|

|

| Gatehouse in 2008 |

The Old Entrance to Woodlawn in 2008 |

The Protestant Church at Kilconnel no longer exists, and all that remains is the graveyard in the corner of the Old Rectory garden on the road towards Aughrim. Local people no longer knew that there had been a Church of Ireland in the village. We had to chase away the donkey to find the gravestones in 1975. Stephen's grave was there under a yew tree. It records his death on 9th June 1886 (also buried there are his children Robert and Elizabeth). Strangely by 2008 the Irish Government has embarked on a "clean up the countryside" offensive, and we found then the churchyard was maintained to the extent of now being marked and the grass kept down.

|

|

|

| Stephen Grant's grave in 2008 |

The Old Rectory at Kilconnel |

|

|

|

| Stephen Grant's grave in 2008 |

Stephen Grant's grave in 2008 |

Times must have been hard for a family growing up with first the famine and then the land wars. Apart from Robert and Elizabeth, the rest of his children left. First John to Bywell, Northumberland in about 1864, followed by his brothers Charles, Richard and Stephen in the early 1870's. Richard and James were later to go to Australia. Anne married twice and went to Akron, Ohio. William and Thomas went to Dublin to get work. Only the two youngest of his children, who remained unmarried, Robert and Elizabeth, stayed at home.

The "castle" gate lodge that was the Grants home from around 1868 till 1935 is in 2008, like Woodlawn House itself, now in ruins. Today there are no Grants in the area, all have moved away..